The funniest and most revealing scene in the new biopic about Usain Bolt shows the global superstar zooming up and down on a Segway, singing to himself in a poky hotel room.

It’s three in the morning, and he is sffering insomnia before a race. Glamorous, it ain’t. The hotel room is too small to swing a cat and looks no posher than a Travelodge.

It’s a fascinating moment because it shows us two things we perhaps did not realise about the fastest man of all time: his life is surprisingly basic; and he suffers from nerves.

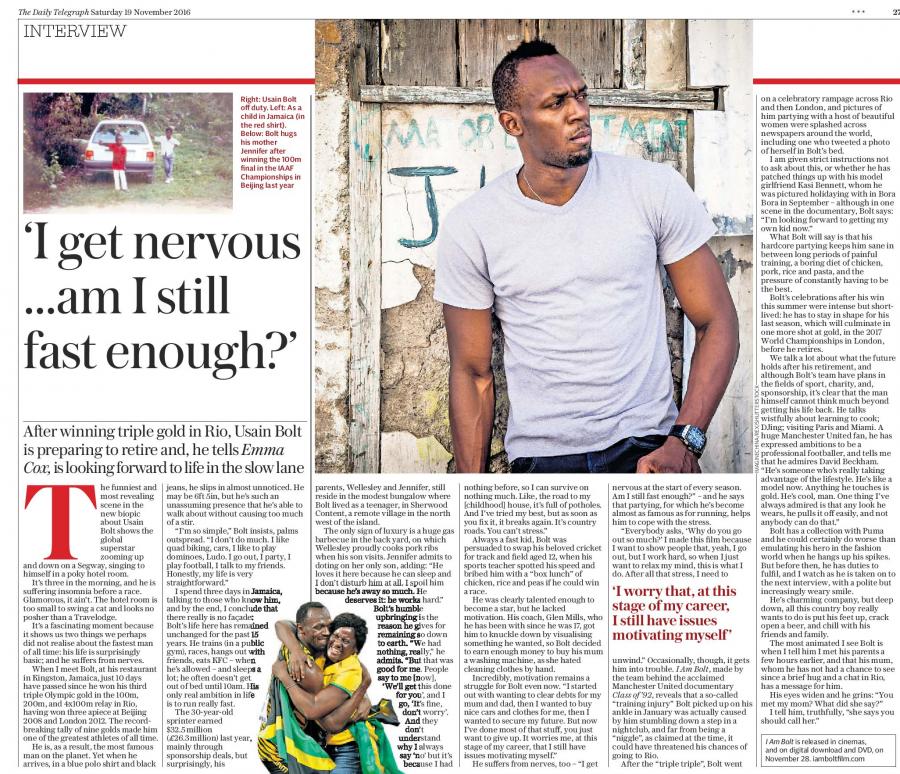

When I meet Bolt, at his restaurant in Kingston, Jamaica, just 10 days have passed since he won his third triple Olympic gold in the 100m, 200m, and 4x100m relay in Rio, having won three apiece at Beijing 2008 and London 2012. The record- breaking tally of nine golds made him one of the greatest athletes of all time.

He is, as a result, the most famous man on the planet. Yet when he arrives, in a blue polo shirt and black

jeans, he slips in almost unnoticed. He may be 6ft 5in, but he’s such an unassuming presence that he’s able to walk about without causing too much of a stir.

“I’m so simple,” Bolt insists, palms outspread. “I don’t do much. I like quad biking, cars, I like to play dominoes, Ludo. I go out, I party, I play football, I talk to my friends. Honestly, my life is very straightforward.”

I spend three days in Jamaica, talking to those who know him, and by the end, I conclude that there really is no façade:

Bolt’s life here has remained unchanged for the past 15 years. He trains (in a public gym), races, hangs out with friends, eats KFC – when he’s allowed – and sleeps a lot; he often doesn’t get

out of bed until 10am. His only real ambition in life is to run really fast.

The 30-year-old sprinter earned $32.5 million (£26.3 million) last year, mainly through sponsorship deals, but surprisingly, his parents, Wellesley and Jennifer, still reside in the modest bungalow where Bolt lived as a teenager, in Sherwood Content, a remote village in the north west of the island.

The only sign of luxury is a huge gas barbecue in the back yard, on which Wellesley proudly cooks pork ribs when his son visits. Jennifer admits to doting on her only son, adding: “He loves it here because he can sleep and I don’t disturb him at all. I spoil him because he’s away so much. He

deserves it: he works hard.” Bolt’s humble upbringing is the reason he gives for remaining so down to earth. “We had nothing, really,” he admits. “But that was good for me. People say to me [now], ‘We’ll get this done for you’, and I go, ‘It’s fine, don’t worry’. And they don’t understand why I always say ‘no’ but it’s because I had nothing before, so I can survive on nothing much. Like, the road to my [childhood] house, it’s full of potholes. And I’ve tried my best, but as soon as you x it, it breaks again. It’s country roads. You can’t stress.”

Always a fast kid, Bolt was persuaded to swap his beloved cricket for track and eld aged 12, when his sports teacher spotted his speed and bribed him with a “box lunch” of chicken, rice and peas if he could win a race.

He was clearly talented enough to become a star, but he lacked motivation. His coach, Glen Mills, who he has been with since he was 17, got him to knuckle down by visualising something he wanted, so Bolt decided to earn enough money to buy his mum a washing machine, as she hated cleaning clothes by hand.

Incredibly, motivation remains a struggle for Bolt even now. “I started out with wanting to clear debts for my mum and dad, then I wanted to buy nice cars and clothes for me, then I wanted to secure my future. But now I’ve done most of that stu , you just want to give up. It worries me, at this stage of my career, that I still have issues motivating myself.”

He suffers from nerves, too – “I get nervous at the start of every season. Am I still fast enough?” – and he says that partying, for which he’s become almost as famous as for running, helps him to cope with the stress.

“Everybody asks, ‘Why do you go out so much?’ I made this lm because I want to show people that, yeah, I go out, but I work hard, so when I just want to relax my mind, this is what I do. After all that stress, I need to

unwind.” Occasionally, though, it gets him into trouble. I Am Bolt, made by the team behind the acclaimed Manchester United documentary Class of ’92, reveals that a so-called “training injury” Bolt picked up on his ankle in January was actually caused by him stumbling down a step in a nightclub, and far from being a “niggle”, as claimed at the time, it could have threatened his chances of going to Rio.

After the “triple triple”, Bolt went on a celebratory rampage across Rio and then London, and pictures of him partying with a host of beautiful women were splashed across newspapers around the world, including one who tweeted a photo of herself in Bolt’s bed.

I am given strict instructions not to ask about this, or whether he has patched things up with his model girlfriend Kasi Bennett, whom he was pictured holidaying with in Bora Bora in September – although in one scene in the documentary, Bolt says: “I’m looking forward to getting my own kid now.”

What Bolt will say is that his hardcore partying keeps him sane in between long periods of painful training, a boring diet of chicken, pork, rice and pasta, and the pressure of constantly having to be the best.

Bolt’s celebrations after his win this summer were intense but short- lived: he has to stay in shape for his last season, which will culminate in one more shot at gold, in the 2017 World Championships in London, before he retires.

We talk a lot about what the future holds after his retirement, and although Bolt’s team have plans in the elds of sport, charity, and, sponsorship, it’s clear that the man himself cannot think much beyond getting his life back. He talks wistfully about learning to cook; DJing; visiting Paris and Miami. A huge Manchester United fan, he has expressed ambitions to be a professional footballer, and tells me that he admires David Beckham. “He’s someone who’s really taking advantage of the lifestyle. He’s like a model now. Anything he touches is gold. He’s cool, man. One thing I’ve always admired is that any look he wears, he pulls it o easily, and not anybody can do that.”

Bolt has a collection with Puma and he could certainly do worse than emulating his hero in the fashion world when he hangs up his spikes. But before then, he has duties to ful l, and I watch as he is taken on to the next interview, with a polite but increasingly weary smile.

He’s charming company, but deep down, all this country boy really wants to do is put his feet up, crack open a beer, and chill with his friends and family.

The most animated I see Bolt is when I tell him I met his parents a few hours earlier, and that his mum, whom he has not had a chance to see since a brief hug and a chat in Rio, has a message for him.

His eyes widen and he grins: “You met my mom? What did she say?”

I tell him, truthfully, “she says you should call her.”

I Am Bolt is released in cinemas, and on digital download and DVD, on November 28